Contemporary African Art’s Hard-won Rise to the Main Stage

The continent is brimming with artists, and not just El Anatsui, who for the last 40 years mostly has been the only artist that Westerners can cite as the African artist from the second-largest continent. While Anatsui, wonderful in so many ways, couldn’t be a better-suited ambassador, his bottle-capped sculptural murals illustrate, as the Nigerian proverb sums up, that “a single man can not build a house.” The house is, instead, a homegrown network of engaged and dynamic art practices, which have been rigorously developing without the aid of traditional art world avenues: collectors, galleries, and art schools. (Though, those avenues are, for the most part, what is leading the West to acknowledge Africa’s scene.)

-

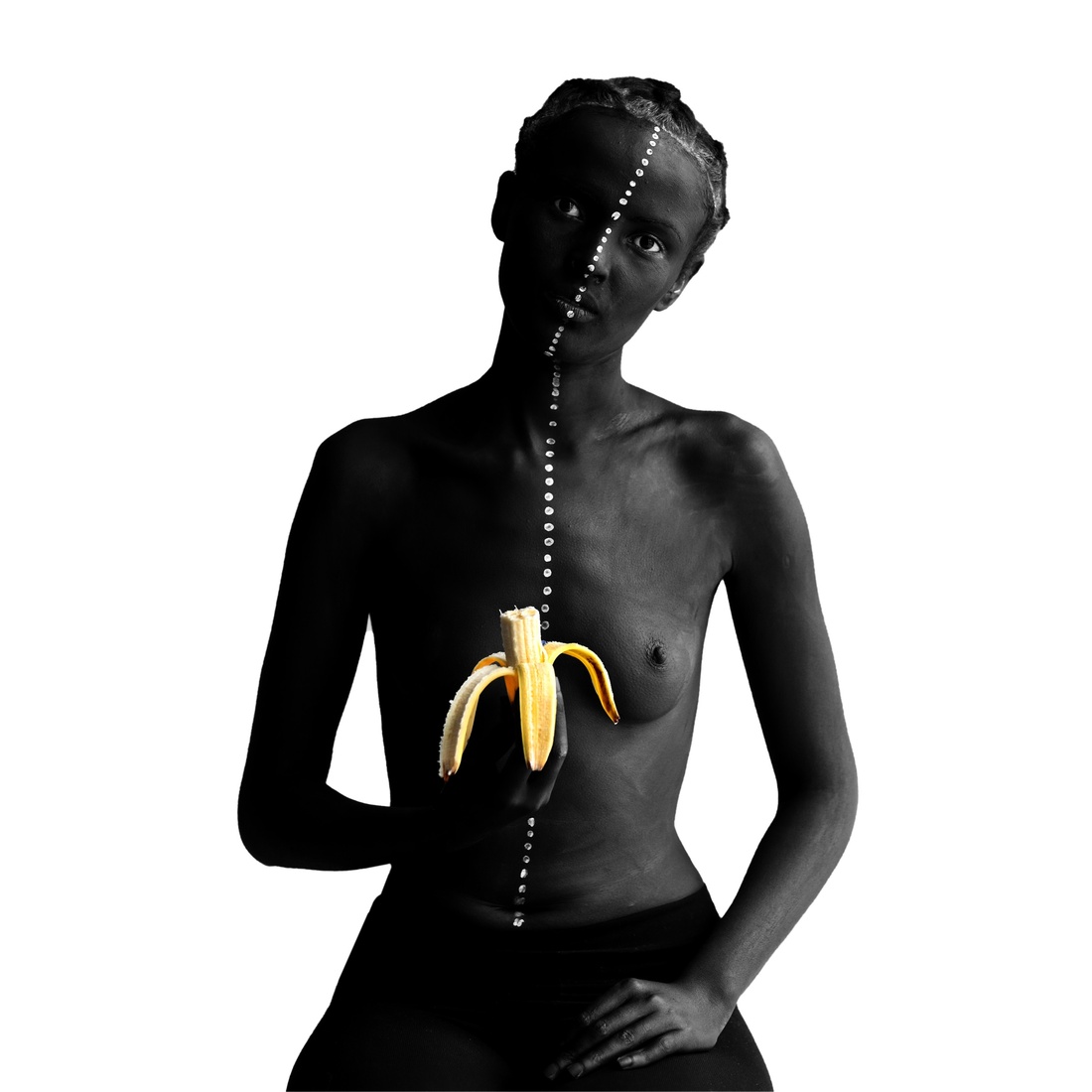

Halida Boughriet, Diner des anonymes from the series Pandora, 2014; Ephrem Solomon Tegegn, Untitled from the series Forbidden Fruit, 2014. Courtesy of Richard Taittinger Gallery.

Nigerian-born artist, art historian, and curator Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi knows the landscape well and has devised an impressive survey of it at New York’s Richard Taittinger Gallery. “One wonders what exactly is African art?” says Smooth, as he is known personally and professionally. “When you walk into this space none of the works look like what people perceive African art to be.” The curator explains that, generally, there’s an expectation “that contemporary artists of Africa should at least convey a sense of the continent.” Titled “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” the show takes its name from the eponymous 1967 Sidney Poitier film and hinges upon a cultural critique by famed Princeton art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, who wrote, “Folks can’t seem to come to terms with the fact that African artists have now taken and secured their seat at the dinner table, invited or not!”

To skeptics and insiders, Okeke-Agulu’s observation may read as hyperbole. But in fact, it’s only been in the last few years that the West has taken stock of the African art scene on any calculable scale. Take Bonhams in London, still the only major auction house to have a dedicated contemporary African arts sale, having consecrated the category in 2007. (With gross 2013–2014 sales generating a mere £1.6 million, it’s still a fledgling sector, and 50% of the buyers are from the African continent.) Likewise, in the primary market sector, 1:54 is the only dedicated African art fair in operation, with a two-year-old stint in London and a first spin in New York this past May.

-

Aida Muluneh, The Wolf You Feed (Part Three), 2014. Courtesy of Richard Taittinger Gallery.

Smooth’s home country, Nigeria, has the continent’s strongest collector base and wealthiest patrons. With South Africa, it comprises half of Africa’s billionaires. Where there is money, there is art. “When there’s an interest at home, it affects the value,” adds Smooth. And make no mistake, Angola, which won the 2013 Venice Biennale Golden Lion, essentially became discovered as an art town once the oil boom hit and local artists like Nástio Mosquito found Western collectors. “Obviously there’s a massive interest in contemporary African art, or artists of African descent, because of the way of the market works,” continues Smooth. “I, in particular, refrain from the rise of the ‘African artist,’ but it’s a reality, there is a rise in interest.”

-

Sam Hopkins, Logos of Non Profit Organisations working in Kenya (some of which are imaginary), 2010-ongoing. Courtesy of Richard Taittinger Gallery.

At 36, Smooth’s own career reflects the peripatetic and diasporic nature of the African arts scene. He grew up in Enugu, apprenticed under Anatsui, studied in South Africa and Atlanta, and has continued his scholarship and curatorial duties at Dartmouth where he’s the curator of African art at the universities Hood Museum. The crux of the paradox of contemporary African art is such: globalization versus ghettoization, a word “we want to refrain from using and that’s the basis of this exhibit. It’s the ‘burden of Africanness,’ which is what we call ghettoization,” he explains. “You don’t find markers that are “African” but there are mediated tendencies. You have to look for tropes that play in the market. The trope, or the burden, of Africanness is what collectors are looking for,” he continues. To a simple eye (or mind) those tropes are the familiar tribal masks, costumes, and other postcard-variety observations about “native” Africa.

“Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” exposes a current trend across much of African contemporary, works that “address those contexts of familiarity but at the same time transcend and consider the universal,” explains the curator. In opposition to the object- and photo-based works often seen on the auction block, painting is the show’s primary medium. Included are the psychologically complex oil paintings of Kenya-based Beatrice Wanjiku and Ivory Coast-born, Paris-based Gopal Dagnogo and the searing mixed-media collage of NGO logos by Kenya-based Sam Hopkins. There are also stunning photographic collages by Madagascar-born Amalia Ramanankirahina and haunting politically charged photographs by Algerian Amina Menia.

-

Amalia Ramanankirahina, Cousins from the series Portraits de Famille (Family Portraits), 2013; Amina Menia, Ziama from the series Chrysanthèmes, 2009-ongoing. Courtesy of Richard Taittinger Gallery.

The themes posited in these works reference anchors of African identity but also take on more human and art historical questions as well. While it’s important that these artists are African, their works wrestle with humanity. “There is tendency to look at the work of Jeff Koons as international, but his work is American,” says Smooth, as a contrast. “What he reflects in his work is American pop culture. So why would one situate Koons in a universalist practice and then try to fit an African artist in a box? It’s simply wrong.” Smooth then added an anecdote, which in essence sums up the status of African arts at the moment: “I remember a conversation Aubrey Williams had with Picasso, who looked at Guyanese Williams and said, ‘you have a fine African head.’ It tells you that there’s a chasm.”

—Julie Baumgardner